With every new day of the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems we discover another complication related to the novel coronavirus.

Early on, collateral damage to the heart, lungs, digestive system, and other organs emerged as life-threating side effects to the “cytokine storm” triggered by the virus in some patients.

The virus also puts cognitive and physical functions at risk, and in some cases, it endangers one of the body’s most delicate instruments – your voice box.

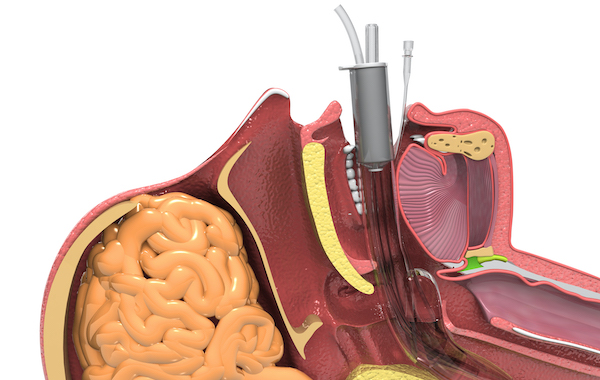

Approximately 19% of patients who get COVID-19 are hospitalized, and about 5% ending up in the intensive care unit, potentially needing intubation, according to the CDC. This is when the doctor places a breathing tube in your mouth, down your throat and past your vocal cord (vocal fold) structures into your windpipe (trachea).

The tube is then connected to a ventilator – a life-support machine that helps you breathe, allowing time for inflammation in the lungs to subside and heal. We only use intubation for respiratory emergencies such as severe COVID-19 infection when the patient is unlikely to survive without it. However, prolonged intubation has definite drawbacks, such as potential damage to your vocal system and upper airway. Complications can include hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, and trouble breathing. In severe cases, patients develop significant vocal fold and airway scarring that could require multiple surgeries to repair.

As an academic medical center, UT Southwestern has expertise in intubation best practices to reduce the risk of vocal fold and airway scarring. We also can potentially avoid damage by converting patients to a tracheostomy – a breathing support tube that bypasses the vocal folds and upper airway if it appears that the patient will be on the ventilator for a prolonged period of time.

Your voice is one of your most important communication tools, especially during the pandemic since we are relying on phone and video calls to communicate with loved ones and colleagues.

The best way to protect yourself and your voice box is to avoid COVID-19 infection and reduce the risk of exposing others to the virus. While about 2.3% of people who get COVID-19 die from it, many more suffer costly, ongoing medical problems after infection.

The Making of a COVID-19 Vaccine

See how the complex process works and how it has been accelerated to combat the pandemic.

Vocal complications from intubation

It's common to experience hoarseness after being intubated for a surgical procedure or for a severe respiratory illness such as the flu, pneumonia, or COVID-19. Placement of the endotracheal tube can irritate the throat tissue, making your throat sore and your voice sound raspy. Typically, hoarseness resolves in a few days. Many patients also experience mild throat swelling or edema after a breathing tube is removed. These symptoms of irritation and swelling can lead to coughing or clearing your throat more frequently, further irritating the vocal system.

More serious complications, however, can arise after long-term or poorly executed intubation:

- Lacerations/injury: Cuts or nicks in the throat tissue or vocal folds from the breathing tube.

- Pressure on the larynx: When the breathing tube presses against the back of your larynx, or voice box, and upper airway, causing tissue damage.

- Arytenoid dislocation or subluxation: These conditions occur when the breathing tube inadvertently moves the joint that helps the vocal folds open and close, allowing you to talk and breath.

Over time, these issues can lead to scarring in the upper airway or vocal fold region that can interfere with talking, swallowing, and even breathing.

Diagnosis and initial treatment

To diagnose vocal fold injury or scarring, we will examine the back of your throat with a lighted device called a laryngoscope. This tool helps us get a clear, magnified view of your larynx to visualize abnormal tissue.

Sometimes, voice therapy can help shrink scar tissue or abnormal growths on the vocal folds. Our speech-language pathologists can help you learn breathing, speaking, and swallowing techniques to optimize your condition and prevent further damage while allowing the body to heal.

If therapy alone isn't enough, we can remove the growths through surgery – a delicate process performed through the mouth. Scar tissue of the vocal folds or upper airway that can develop from breathing tubes typically requires surgical intervention for removal; sometimes multiple procedures are required.

How we remove vocal fold scar tissue

Prior to surgery, you will be tested for COVID-19. If you are infected, we will reschedule. If your test is negative, we can proceed.

In the operating room, you will be placed under general anesthesia. The procedure is performed through the mouth with no incisions on the neck. Using a laser, we will remove as much of the scar tissue as possible. Sometimes a balloon is used to dilate or stretch out the region of scarring.

Also, we will inject steroids into the affected area to try and prevent the scar tissue from coming back. Unfortunately, the scar tissue does grow back in many patients, who will then require additional surgery to manage the condition.

After surgery, you will need to avoid smoking, eating spicy foods, or becoming dehydrated, which can lead to a sore throat and further damage to the area. Patients typically recover from surgery within a week.

If you choose not to have surgery, your scar tissue may get worse, limiting your ability to talk, swallow and possibly even breathe.

More potential side effects of intubation for COVID-19

Ventilators are lifesaving machines. But being on a ventilator is not a natural state for the human body:

- It requires heavy sedation, particularly for patients with severe inflammation in their lungs.

- The vocal system and upper airway are put at risk whenever a plastic tube is placed in your throat.

- There are potential dangers of infection.

- Physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments increase the longer a patient remains on a ventilator. Patients with COVID-19 who require mechanical ventilation often continue to need it for 2-3 weeks before breathing on their own again.

- Delirium and PTSD-like (post-traumatic stress disorder) symptoms are concerns during and after recovery and we take steps to reduce those complications in the intensive care unit.

At William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital, we closely monitor patients on ventilators for COVID-19 infection. We also have several strategies to reduce risks. Those include:

- Lightening the sedatives: Every morning, we reduce the patient’s pain medication levels to check their lung function and breathing. This also helps potentially reduce their time on the ventilator and their risk of disorientation.

- Adjusting positions: We’ve found that many patients with COVID-19 do better on ventilators if they’re positioned on their stomachs for periods of time. This position takes pressure off key parts of the lungs and reduces stress on the heart and diaphragm.

- Converting to tracheostomy: This surgical procedure involves making a small incision in the neck below the vocal folds and inserting a tube into the trachea – bypassing the vocal folds. It can provide a more secure airway and allows us to wake the patient more often to fend off delirium and, hopefully, wean them off mechanical support. But the patient must be stable enough for surgery, so tracheostomy is not typically an option in the early stage of severe respiratory distress.

We do everything we can to keep our patients with COVID-19 comfortable in the ICU, but being on a ventilator is an unnatural situation. Complications can last long after the virus is gone, including PTSD-like symptoms sometimes called post intensive care syndrome (PICS).

If you need any more reason to follow the now familiar strategies to reduce the spread of COVID-19 – wear a mask, avoid large gatherings, and practice good hand hygiene – consider the daunting prospect of needing a machine to breathe.

Your body doesn't want this unpredictable virus. And you don't want a tube in your throat, if you can avoid it. Please do your part to protect yourselves and others against COVID-19. Let's get through this pandemic together.

To see a doctor about your vocal health, call 214-645-8300 or request an appointment online.